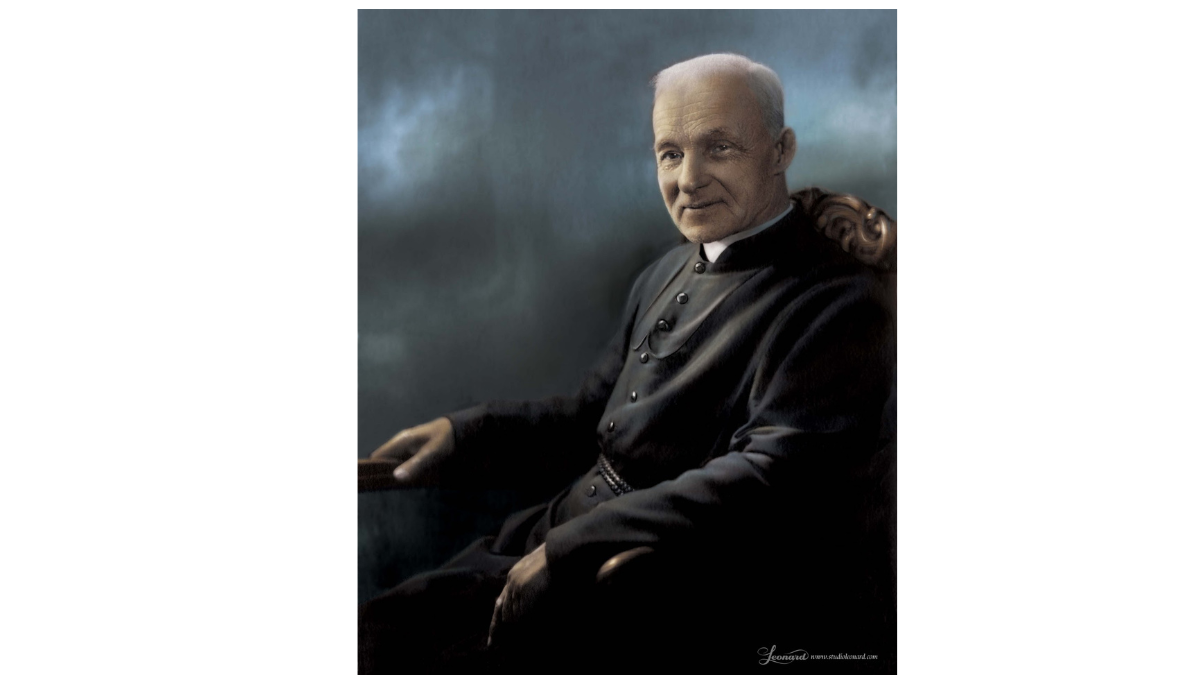

St. Andre Bessette

| Feast day | September 25 |

| Patron | of Cork, Diocese of Cork |

| Birth | 550 |

| Death | 620 |

When Alfred Bessette came to the Holy Cross Brothers in 1870, he carried with him a note from his pastor saying, “I am sending you a saint.” The Brothers found that difficult to believe. Chronic stomach pains had made it impossible for Alfred to hold a job very long and since he was a boy he had wandered from shop to shop, farm to farm, in his native Canada and in the United States, staying only until his employers found out how little work he could do. The Holy Cross Brothers were teachers and, at 25, Alfred still did not know how to read and write. It seemed as if Alfred approached the religious order out of desperation, not vocation.

Alfred was desperate, but he was also prayerful and deeply devoted to God and Saint Joseph. He may have had no place left to go, but he believed that was because this was the place he felt he should have been all along.

The Holy Cross Brothers took him into the novitiate but soon found out what others had learned — as hard as Alfred, now Brother Andre, wanted to work, he simply wasn’t strong enough. They asked him to leave the order, but Andre, out of desperation again, appealed to a visiting bishop who promised him that Andre would stay and take his vows.

After his vows, Brother Andre was sent to Notre Dame College in Montreal (a school for boys age seven to twelve) as a porter. There his responsibilities were to answer the door, to welcome guests, find the people they were visiting, wake up those in the school, and deliver mail. Brother Andre joked later, “At the end of my novitiate, my superiors showed me the door, and I stayed there for forty years.”

In 1904, he surprised the Archbishop of Montreal if he could, by requesting permission to, build a chapel to Saint Joseph on the mountain near the college. The Archbishop refused to go into debt and would only give permission for Brother Andre to build what he had money for. What money did Brother Andre have? Nickels he had collected as donations for Saint Joseph from haircuts he gave the boys. Nickels and dimes from a small dish he had kept in a picnic shelter on top of the mountain near a statue of St. Joseph with a sign “Donations for St. Joseph.” He had collected this change for years but he still had only a few hundred dollars. Who would start a chapel now with so little funding?

Andre took his few hundred dollars and built what he could … a small wood shelter only fifteen feet by eighteen feet. He kept collecting money and went back three years later to request more building. The wary Archbishop asked him, “Are you having visions of Saint Joseph telling you to build a church for him?”

Brother Andre reassured him. “I have only my great devotion to St. Joseph to guide me.”

The Archbishop granted him permission to keep building as long as he didn’t go into debt. He started by adding a roof so that all the people who were coming to hear Mass at the shrine wouldn’t have to stand out in the rain and the wind. Then came walls, heating, a paved road up the mountain, a shelter for pilgrims, and finally a place where Brother Andre and others could live and take care of the shrine — and the pilgrims who came – full-time. Through kindness, caring, and devotion, Brother Andre helped many souls experience healing and renewal on the mountaintop. There were even cases of physical healing. But for everything, Brother Andre thanked St. Joseph.

Despite financial troubles, Brother Andre never lost faith or devotion. He had started to build a basilica on the mountain but the Depression had interfered. At ninety-years old he told his co-workers to place a statue of St. Joseph in the unfinished, unroofed basilica. He was so ill he had to be carried up the mountain to see the statue in its new home. Brother Andre died soon after on January 6, and didn’t live to see the work on the basilica completed. But in Brother Andre’s mind it never would be completed because he always saw more ways to express his devotion and to heal others. As long as he lived, the man who had trouble keeping work for himself, would never have stopped working for God.

On December 19, 2009, Pope Benedict XVI promulgated a decree recognizing a second miracle at Blessed André’s intercession and on October 17, 2010, Pope Benedict XVI formally declared sainthood for Blessed Andre.

In His Footsteps:

Brother Andre didn’t mind starting small.

Think of some service you have longed to perform for God and God’s people, but that you thought was too overwhelming for you. What small bit can you do in this service? If you can’t afford to give a lot of money to a cause, just give a little. If you can’t afford hours a week in volunteering, try an hour a month on a small task. It is amazing how those small steps can lead you up the mountain as they did for Brother Andre.

Prayer:

Blessed Brother Andre, your devotion to Saint Joseph is an inspiration to us. You gave your life selflessly to bring the message of his life to others. Pray that we may learn from Saint Joseph, and from you, what it is like to care for Jesus and do his work in the world. Amen

Views: 2