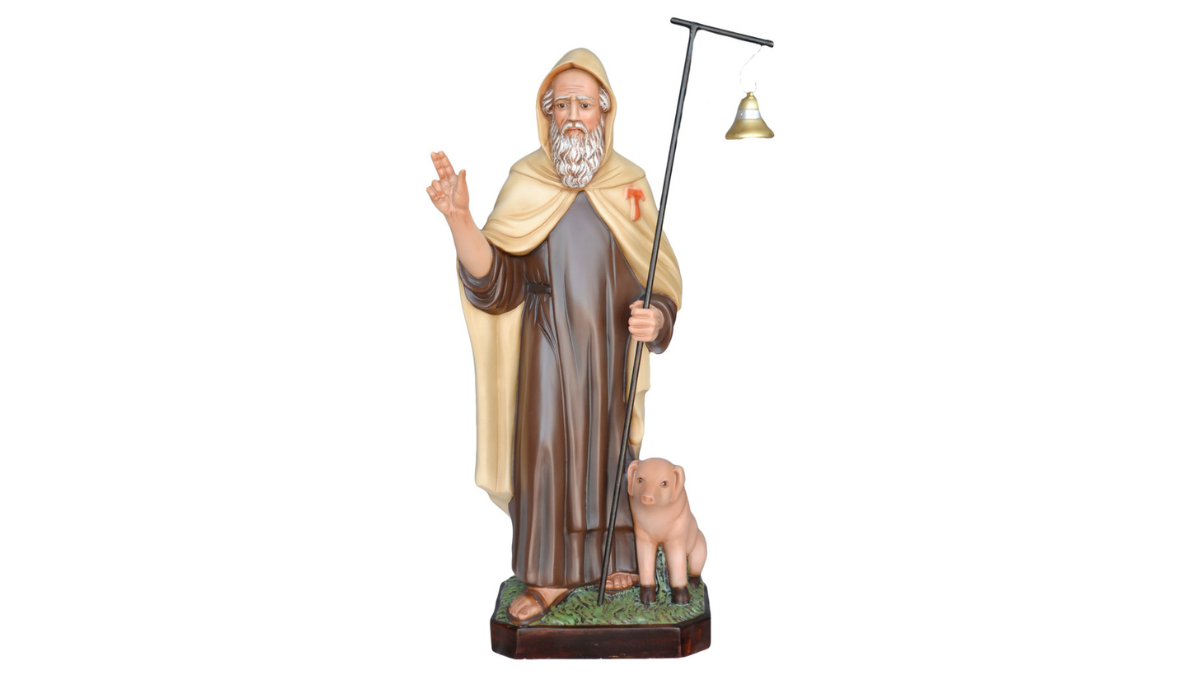

St. Anthony the Abbot

| Feast day | September 25 |

| Patron | of Cork, Diocese of Cork |

| Birth | 550 |

| Death | 620 |

Two Greek philosophers ventured out into the Egyptian desert to the mountain where Anthony lived. When they got there, Anthony asked them why they had come to talk to such a foolish man? He had reason to say that — they saw before them a man who wore a skin, who refused to bathe, who lived on bread and water. They were Greek, the world’s most admired civilization, and Anthony was Egyptian, a member of a conquered nation. They were philosophers, educated in languages and rhetoric. Anthony had not even attended school as a boy and he needed an interpreter to speak to them. In their eyes, he would have seemed very foolish.

But the Greek philosophers had heard the stories of Anthony. They had heard how disciples came from all over to learn from him, how his intercession had brought about miraculous healings, how his words comforted the suffering. They assured him that they had come to him because he was a wise man.

Anthony guessed what they wanted. They lived by words and arguments. They wanted to hear his words and his arguments on the truth of Christianity and the value of ascetism. But he refused to play their game. He told them that if they truly thought him wise, “If you think me wise, become what I am, for we ought to imitate the good. Had I gone to you, I should have imitated you, but, since you have come to me, become what I am, for I am a Christian.”

Anthony’s whole life was not one of observing, but of becoming. When his parents died when he was eighteen or twenty he inherited their three hundred acres of land and the responsibility for a young sister. One day in church, he heard read Matthew 19:21: “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.” Not content to sit still and meditate and reflect on Jesus’ words he walked out the door of the church right away and gave away all his property except what he and his sister needed to live on. On hearing Matthew 6:34, “So do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today’s trouble is enough for today,” he gave away everything else, entrusted his sister to a convent, and went outside the village to live a life of praying, fasting, and manual labor. It wasn’t enough to listen to words, he had to become what Jesus said.

Every time he heard of a holy person he would travel to see that person. But he wasn’t looking for words of wisdom, he was looking to become. So if he admired a person’s constancy in prayer or courtesy or patience, he would imitate it. Then he would return home.

Anthony went on to tell the Greek philosophers that their arguments would never be as strong as faith. He pointed out that all rhetoric, all arguments, no matter how complex, how well-founded, were created by human beings. But faith was created by God. If they wanted to follow the greatest ideal, they should follow their faith.

Anthony knew how difficult this was. Throughout his life he argued and literally wrestled with the devil. His first temptations to leave his ascetic life were arguments we would find hard to resist — anxiety about his sister, longings for his relatives, thoughts of how he could have used his property for good purposes, desire for power and money. When Anthony was able to resist him, the devil then tried flattery, telling Anthony how powerful Anthony was to beat him. Anthony relied on Jesus’ name to rid himself of the devil. It wasn’t the last time, though. One time, his bout with the devil left him so beaten, his friends thought he was dead and carried him to church. Anthony had a hard time accepting this. After one particular difficult struggle, he saw a light appearing in the tomb he lived in. Knowing it was God, Anthony called out, “Where were you when I needed you?” God answered, “I was here. I was watching your struggle. Because you didn’t give in, I will stay with you and protect you forever.”

With that kind of assurance and approval from God, many people would have settled in, content with where they were. But Anthony’s reaction was to get up and look for the next challenge — moving out into the desert.

Anthony always told those who came to visit him that the key to the ascetic life was perseverance, not to think proudly, “We’ve lived an ascetic life for a long time” but treat each day as if it were the beginning. To many, perseverance is simply not giving up, hanging in there. But to Anthony perseverance meant waking up each day with the same zeal as the first day. It wasn’t enough that he had given up all his property one day. What was he going to do the next day?

Once he had survived close to town, he moved into the tombs a little farther away. After that he moved out into the desert. No one had braved the desert before. He lived sealed in a room for twenty years, while his friends provided bread. People came to talk to him, to be healed by him, but he refused to come out. Finally they broke the door down. Anthony emerged, not angry, but calm. Some who spoke to him were healed physically, many were comforted by his words, and others stayed to learn from him. Those who stayed formed what we think of as the first monastic community, though it is not what we would think of religious life today. All the monks lived separately, coming together only for worship and to hear Anthony speak.

But after awhile, too many people were coming to seek Anthony out. He became afraid that he would get too proud or that people would worship him instead of God. So he took off in the middle of the night, thinking to go to a different part of Egypt where he was unknown. Then he heard a voice telling him that the only way to be alone was to go into the desert. He found some Saracens who took him deep into the desert to a mountain oasis. They fed him until his friends found him again.

Anthony died when he was one hundred and five years old. A life of solitude, fasting, and manual labor in the service of God had left him a healthy, vigorous man until very late in life. And he never stopped challenging himself to go one step beyond in his faith.

Saint Athanasius, who knew Anthony and wrote his biography, said, “Anthony was not known for his writings nor for his worldly wisdom, nor for any art, but simply for his reverence toward God.” We may wonder nowadays at what we can learn from someone who lived in the desert, wore skins, ate bread, and slept on the ground. We may wonder how we can become him. We can become Anthony by living his life of radical faith and complete commitment to God.

In His Footsteps: Fast for one day, if possible, as Anthony did, eating only bread and only after the sun sets. Pray as you do that God will show you how dependent you are on God for your strength.

Prayer: Saint Anthony, you spoke of the importance of persevering in our faith and our practice. Help us to wake up each day with new zeal for the Christian life and a desire to take the next challenge instead of just sitting still. Amen.

Views: 1